Why Do My Sourdough Loaves Spread When Tipped Out of Bannetons?

/Help! My sourdough is spreading when I take them out of the proofing bannetons!

After waiting almost 24 hours to see how your bread will turn out, it can be most disappointing to get to the baking part, only to turn your loaves out of the proofing baskets and find they’re spreading and losing shape.

Why does this happen? Why doesn’t dough stay nicely in its shape when turned out of bannetons?

There are a number of reasons this could happen. I know, I wish it was a one step simple solution too, but part of the fun of sourdough is getting to troubleshoot.

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase using these links, Jennyblogs may receive a small commission, at no extra cost to you. This helps to support Jennyblogs. Where possible, links are prioritized to small businesses and ethically and responsibly made items. For further information see the privacy policy. Grazie!

Let’s start with some of the more common problems:

Dough is over-proofed

Whether bulk fermentation was too long or the final proof was too long, dough that is over-risen and too bubbly will deflate and spread when tipped out of the banneton.

Another sign dough is over-proofed is if the dough is sticky and sticks to the banneton, not wanting to come out despite adequate flouring.

If you’re following a recipe for sourdough, make sure you’re following a bulk ferment that is proper for your dough, temperature, and environment, not the recipe author’s. Watch your dough, not the clock. Question any recipe that tells you to bulk ferment for a specific amount of time when precise temperature is not taken into account.

Inadequate Gluten Development

This simply means the dough was not worked/kneaded enough to hold its shape. This is especially important for loaves that are baked freeform, like classic sourdough; they don’t have the support of bread pan sides to help guide their rise upwards. Without proper gluten development, dough won’t hold its shape well, and instead spread or sag.

From the moment you mix all ingredients together, to stretch and folds and coil folds, you’re working up dough strength. By the end of your last coil fold or stretch and fold, the dough’s gluten should be just about fully developed. One way you can test this is by performing the window pane test. The window pane test is most illuminating when done throughout the bread making process, from the moment the ingredients are barely mixed (to appreciate the complete lack of window pane) all the way up to the end of bulk ferment where ideally, the window pane will be strong. If you achieve a strong windowpane with your dough during bulk ferment but notice that it starts to become less so towards the end of bulk ferment, you may be fermenting your dough too long. The acidity in sourdough can start to break down the strong gluten network if fermented for too long.

Poor Shaping

It’s important to shape sourdough into its final shape securely and tightly with good surface tension. There are many effective ways to do this. You don’t have to do what the next person is doing, pick one that works well for you. Consider the Tartine method, a trifold and rolling, a single or double Caddy Clasp.

If you struggle to get a good shape initially, then try stitching your dough after it’s in the banneton. To do this, shape and place dough into banneton, then wait 10 minutes. Pinch a small piece of dough from one side and stretch it over and attach to the other side. Now start on that side, pinching and stretching across. Work your down the whole loaf until it is all “stitched.” This is an effective way to create more surface tension and help the dough keep its shape. It may not completely fix a poor shape job, but it will help.

Over-hydrated Dough

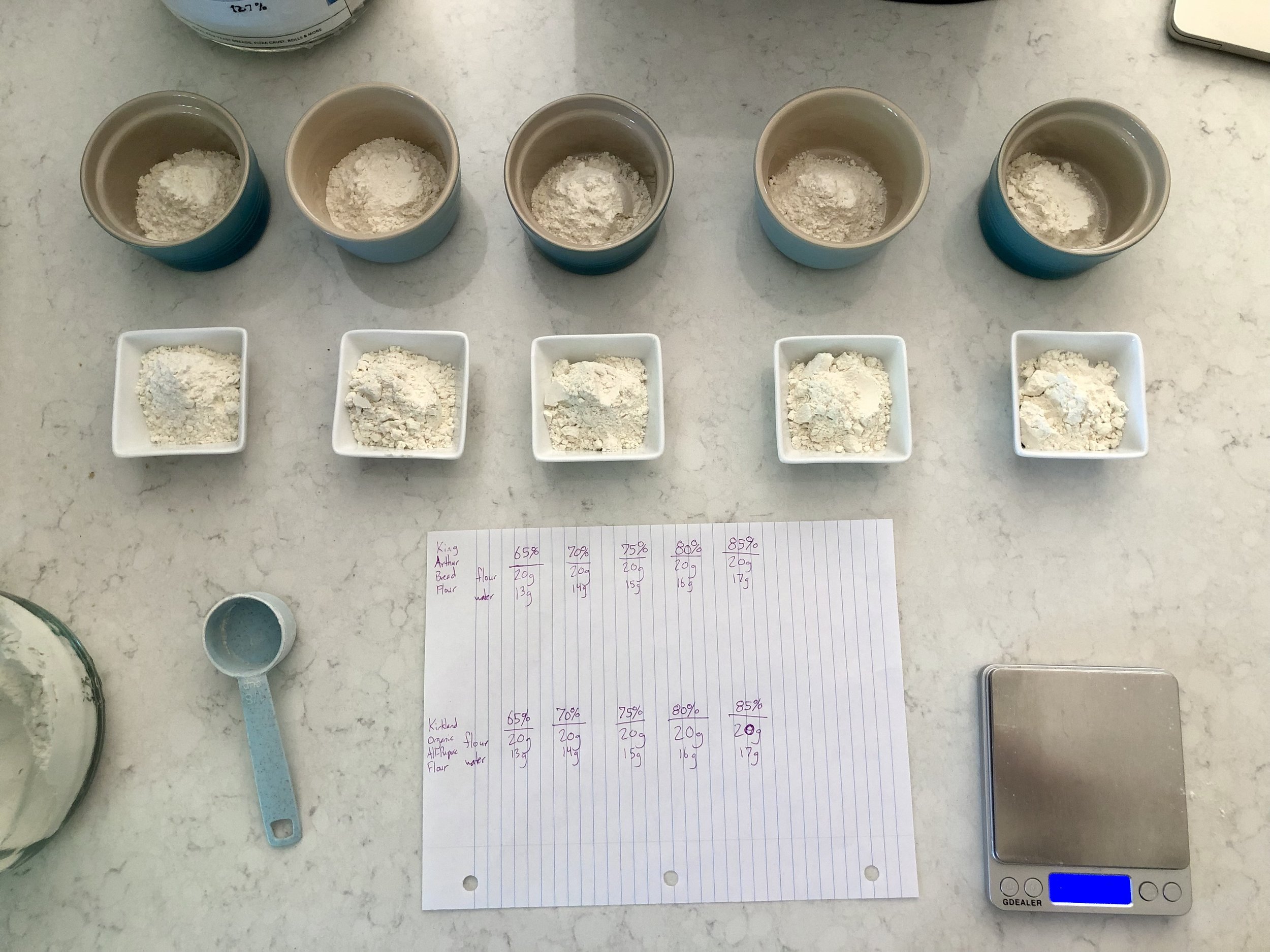

High-hydration doughs are trickier to work with, but can yield a beautiful loaf. However, once the hydration is taken too far for the particular flour being worked with, the dough won’t be able to hold its shape. A bread flour can generally hold more hydration than an all-purpose flour. Whole wheat flours are also “thirsty” flours.

If you desire to work more with higher hydration doughs but wonder how much water you can successfully use with your flour, then try a flour hydration capacity test, as outlined here.

A note here, as higher hydration doughs will naturally spread a bit more than lower hydration loaves when tipped out of bannetons. The key difference is that a high hydration dough using the proper flour, with a healthy starter, proper fermentation times, proper gluten development, and proper shaping will still spring up beautifully in the oven.

Another phenomenon I’ve read about is where the dough will flatten out almost like a pancake when dumped out of the banneton, to the point the baker thinks their loaf is no good, only to bake up into a loaf with impressive oven spring. I’m not sure why this happens to some, but I might venture a guess that it’s a somewhat higher hydration loaf with improper shaping, but a very healthy starter that springs their loaf up despite some possible errors in the process.